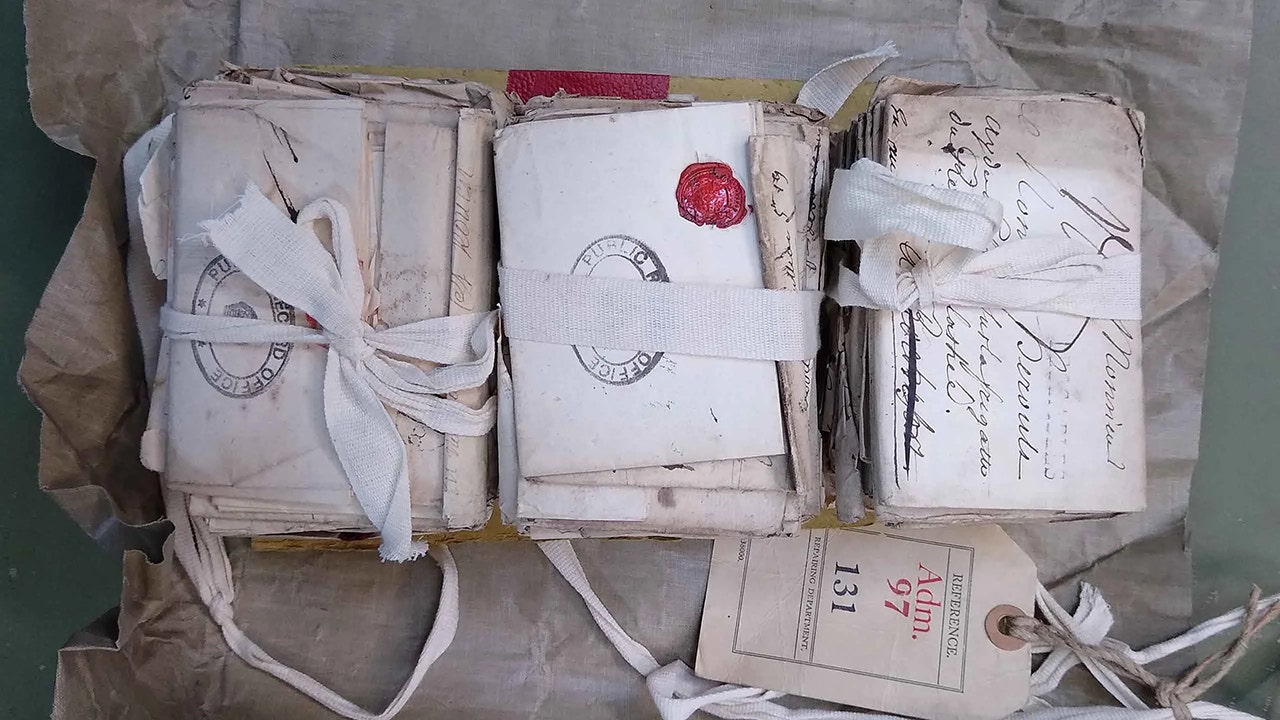

Imagine writing a letter to someone when it was one of the few forms of communication while you were apart – and that letter never made it to whom you intended.That is what happened to more than 100 letters mailed to French sailors from their loved ones, written between 1757 and 1758, seized by Britain’s Royal Navy during the Seven Years’ War, according to the University of Cambridge. “The messages offer extremely rare and moving insights into the loves, lives and family quarrels of everyone from elderly peasants to wealthy officers’ wives,” author Tom Almeroth-Williams writes after they were opened and read for the first time in 265 years.Many of the photographed letters show they were wax-sealed, handwritten and “provide precious new evidence about French women and [laborers], as well as different forms of literacy.” KING CHARLES OUTLINES CONSERVATIVE GOVERNMENT’S AIMS IN FIRST SPEECH TO PARLIAMENT The professor who requested access to the letters says they were in a box held together by ribbon, very small and sealed. (Renaud Morieux/The National Archives)Professor Renaud Morieux from Cambridge University’s history faculty and Pembroke College requested the letters and spent months decoding them before publishing his findings in the academic journal “Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales.””I realized I was the first person to read these very personal messages since they were written. Their intended recipients didn’t get that chance. It was very emotional,” Morieux said. “Today we have Zoom and WhatsApp. In the 18th century, people only had letters but what they wrote about feels very familiar.”The Seven Years’ War lasted from 1756 to 1763. At the time, France commanded some of the world’s finest ships yet lacked experienced sailors. Britain used that knowledge to imprison as many French sailors as it could during the war.The letters were meant to be delivered to those aboard the Galatée, which was sailing from Bordeaux to Quebec in 1758 when it was captured by the British ship the Essex, and sent to Portsmouth. Galatée’s crew was imprisoned, and the ship was sold. LONDON POLICE IN HOT WATER AFTER ADVISER’S ANTI-ISRAEL CHANT REVEALED: REPORT This picture shows a woman named Anne Le Cerf’s loving sign-off to her husband. (Renaud Morieux/The National Archives) Final page of a woman named Marguerite’s letter to her son Nicolas Quesnel, in which she says, “I think I am for the tomb,” dated Jan. 27, 1758. (Renaud Morieux/ The National Archives)CLICK TO GET THE FOX NEWS APPCambridge University says the French postal administration made several failed attempts to deliver the letters to the ship, often arriving too late to ports. When word of the ship’s capture got to them, the letters were forwarded to England, where they were handed to the Admiralty in London.”It’s [agonizing] how close they got,” Morieux said. He believes officials attempted to see if the letters contained any military value but once they determined they only had “family stuff,” they gave up and put them in storage. Intimate details from some of the letters can be read here.

Source link

French love letters confiscated during Seven Years’ War read for first time 265 years later